Negative interest rate swap spreads signal pressure in government debt absorption

Box extracted from Overview chapter "Investor optimism prevails over uncertainty"

Interest rate swaps are contracts in which counterparties agree to exchange a series of fixed rate payments for a series of floating payments linked to a benchmark rate. The swap spread is the difference between the interest rate swap rate and the yield on a government bond of the same maturity. The swap rate refers to the fixed rate in the swap; it reflects expectations of future floating rates and can therefore be interpreted as the price that ensures that both the receiver and the payer of the fixed rate view the contract as fairly priced from the start. Swap rates and bond yields are tied together by arbitrage. Absent costs involved in the arbitrage and compensation for risks, swap spreads should not deviate much from zero. Prior to the Great Financial Crisis, spreads were generally positive, as swap rates exceeded cash bond yields, in part due to some credit risk reflected in the swap rate.

More recently though, the constellation has flipped, with negative swap spreads being increasingly common across currencies and maturities.

More recently though, the constellation has flipped, with negative swap spreads being increasingly common across currencies and maturities.

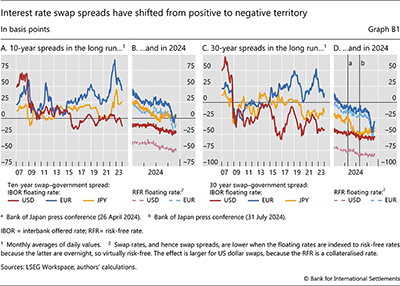

Swap spreads in US dollars were negative for some time post-Great Financial Crisis (Graph B1) but have become more persistent even at 10-year tenors (Graph B1.B). More recently, negative swap spreads have also become more common in other major currencies, such as the euro and Japanese yen (Graph B1.D). Negative swap spreads, at least in theory, represent an arbitrage opportunity, and should therefore be quickly brought back to zero. Market participants could exploit a negative swap spread by holding a government bond funded through repo, paying the fixed rate in the swap and earning the floating, thus pocketing the difference between these rates.

but have become more persistent even at 10-year tenors (Graph B1.B). More recently, negative swap spreads have also become more common in other major currencies, such as the euro and Japanese yen (Graph B1.D). Negative swap spreads, at least in theory, represent an arbitrage opportunity, and should therefore be quickly brought back to zero. Market participants could exploit a negative swap spread by holding a government bond funded through repo, paying the fixed rate in the swap and earning the floating, thus pocketing the difference between these rates.

Negative swap spreads are not arbitraged away because they capture intermediation costs rather than a "free lunch". Negative spreads compensate intermediaries for holding government bonds on their balance sheets and entering swaps as fixed rate payers. Both swap and bond markets are intermediated by bank-affiliated dealers who require remuneration for using their balance sheets and taking on associated risks. When dealers absorb a large amount of bonds, they incur funding costs in the repo market for financing the long bond position. Additionally, they tend to hedge the interest rate risk by paying the fixed swap rate and receiving the floating rate. When doing so, dealers also need to factor in balance sheet costs from internal risk management and prudential rules, as well as opportunity costs of other uses of their balance sheet capacity. If these costs are high enough, dealers will recoup them through a negative swap spread. Moreover, if dealer balance sheets are constrained, non-bank players such as hedge funds may need to be incentivised to step in, deploying repo leverage to assume similar positions as dealers.

Downward pressure on swap spreads can originate either from a greater supply of government bonds in cash markets or a greater demand to receive the fixed rate in swap markets. In cash bond markets, investors' inability or unwillingness to absorb debt issuance or sales by other bond holders at prevailing prices exerts upward pressure on bond yields, pushing swap spreads lower. In swap markets, asset managers, institutional investors and corporate debt issuers are typical receivers of the fixed rate in the swap. The greater these players' demand to receive the fixed rate, the greater the downward pressure on swap rates and hence swap spreads.

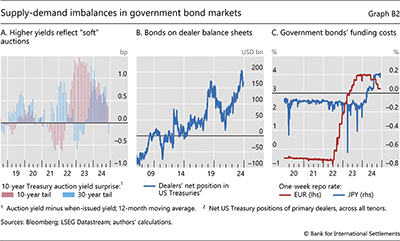

In recent months, pressure points primarily originating in the cash bond markets have caused noticeable imbalances in supply and demand. Recent Treasury auction results underscore this, with some monthly auctions clearing at a higher yield (lower price) than expected since 2022 (Graph B2.A). These "soft" auction results reflect investors' lukewarm interest in absorbing the supply of government debt and that dealer bond inventories have swollen to record levels this year (Graph B2.B).

Negative swap spreads have also emerged more recently in the euro area and Japan. A common driver with the United States is the additional expected bond issuance given the upward trajectory in debt supply. But jurisdiction-specific drivers are also at play. For one, as the euro area and Japanese central banks embarked on quantitative tightening (QT), expectations that the private sector would need to play a bigger marginal role in absorption pushed bond yields higher, compressing swap spreads. The 30-year yen swap spread dropped into deeply negative territory in April, when the Bank of Japan announced the exit from its ultra-loose balance sheet policy. The spread then decompressed in July, when the central bank revealed that the pace of QT would be slower than previously expected. In the euro area, swap spreads tumbled in October, as QT's effects were felt in markets via pressure on bond yields. And the steep fall in euro swap spreads coincided with a drop in the demand to tap the ECB Securities Lending Facility to source collateral (see main text) – a sign that government bond collateral in private hands was no longer scarce.

Another common driver of swap spreads has been the rise in funding costs in repo markets as central banks abandoned negative policy rates. In this case, the ECB was ahead of the Bank of Japan by almost two years (Graph B2.C). Since then, dealers have had to pay positive repo rates to fund their long positions in government bonds. Furthermore, the relative abundance of government bond collateral, due to increased issuance and less central bank heft, has put additional upward pressure on repo rates.

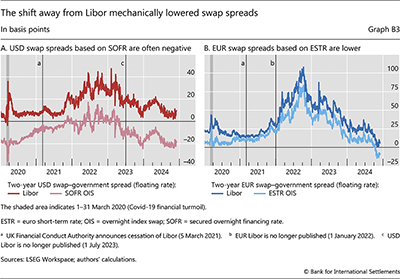

Finally, there are technical reasons for more negative swap spreads, notably the shift in reference rates in swaps away from Libor benchmark interest rates to so-called risk-free rates. Before the switch away from Libor, the swap rate was the fair price at inception of a series of expected future rates that embodied credit risk. Now that swap contracts are referenced to (nearly) risk-free rates in the floating leg, the swap rate itself is lower, which means that swap spreads also will be lower or more negative (Graphs B1.B and B1.D). In fact, the emergence of negative spreads at shorter tenors (eg two years) is mainly due to the shift towards risk-free benchmarks following the cessation of Libor (Graph B3). Benchmarks based on collateralised rates, such as the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR), result in even lower swap rates, and thus more negative swap spreads (Graph B3.A). SOFR-based spreads will also be influenced by repo market developments, as seen in the March 2020 dash for cash episode. ,

,

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS.  Credit risk played a bigger role when swap rates were linked to benchmarks based on unsecured term bank funding rates (eg Libor) and because counterparties in the swap were exposed to each other's credit risk (typically mitigated through collateralisation) – a risk significantly reduced through the shift to central clearing.

Credit risk played a bigger role when swap rates were linked to benchmarks based on unsecured term bank funding rates (eg Libor) and because counterparties in the swap were exposed to each other's credit risk (typically mitigated through collateralisation) – a risk significantly reduced through the shift to central clearing.  S Sundaresan and V Sushko, "Recent dislocations in fixed income derivatives markets", BIS Quarterly Review, December 2015.

S Sundaresan and V Sushko, "Recent dislocations in fixed income derivatives markets", BIS Quarterly Review, December 2015.  See eg N Boyarchenko, P Gupta, N Steele and J Yen, "Negative swap spreads", Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, October 2018; and U Jermann, "Negative swap spreads and limited arbitrage", The Review of Financial Studies, vol 33, no 1, 2019.

See eg N Boyarchenko, P Gupta, N Steele and J Yen, "Negative swap spreads", Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, October 2018; and U Jermann, "Negative swap spreads and limited arbitrage", The Review of Financial Studies, vol 33, no 1, 2019.  See S Klingler and S Sundaresan, "An explanation of negative swap spreads: demand for duration from underfunded pension plans", The Journal of Finance, vol 74, no 2, 2018; and, S Hanson, A Malkhozov and G Venter, "Demand-and-supply imbalance risk and long-term swap spreads", Journal of Financial Economics, vol 154, 103814, 2024.

See S Klingler and S Sundaresan, "An explanation of negative swap spreads: demand for duration from underfunded pension plans", The Journal of Finance, vol 74, no 2, 2018; and, S Hanson, A Malkhozov and G Venter, "Demand-and-supply imbalance risk and long-term swap spreads", Journal of Financial Economics, vol 154, 103814, 2024.  The added sensitivity of long-maturity bonds to interest rate risk is another reason why negative swap spreads tend to be more prevalent at longer maturities.

The added sensitivity of long-maturity bonds to interest rate risk is another reason why negative swap spreads tend to be more prevalent at longer maturities.  See A Schrimpf and V Sushko, "Beyond LIBOR: a primer on the new benchmark rates", BIS Quarterly Review, March 2018; and D Wu and R Jarrow, "The Treasury – SOFR swap spread puzzle explained", 2024, available on SSRN.

See A Schrimpf and V Sushko, "Beyond LIBOR: a primer on the new benchmark rates", BIS Quarterly Review, March 2018; and D Wu and R Jarrow, "The Treasury – SOFR swap spread puzzle explained", 2024, available on SSRN.  Since the discontinuation of Libor, the difference between swap spreads based on the two types of rates is constant, as the ISDA fallback solution for legacy cleared derivatives transactions consists of a constant add-on risk spread.

Since the discontinuation of Libor, the difference between swap spreads based on the two types of rates is constant, as the ISDA fallback solution for legacy cleared derivatives transactions consists of a constant add-on risk spread.