FX trade execution: complex and highly fragmented

The 2019 Triennial Survey shows that trade execution has undergone rapid change, with more diverse participants, new technologies and increasing complexity. Electronification advanced the fastest in dealer-to-customer trading. Dealers and customers navigated a highly fragmented market by leveraging technology to trade across electronic venues. Aspects of FX intermediation tilted more towards non-banks as new market-makers, albeit brokered by top dealers. Bank dealers continued to attract large flows to their own proprietary liquidity pools. Consequently, even though the market grew bigger as a whole, the share of trading activity 'visible' to the broader market declined.1

JEL classification: C42, C82, F31, G12, G15.

For many years, the BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey2 has chronicled changes in the structure of foreign exchange (FX) markets and the way trades are executed, meaning where and how orders are filled. The latest survey shows that trade execution has undergone rapid change. FX trading is turning more electronic, participants are becoming more diverse, and trading venues are multiplying. These innovations have enhanced the speed of trading, offered participants more choices and facilitated a greater variety of trading strategies.

This special feature first describes how FX markets have become increasingly complex and fragmented. It then analyses recent developments in trade execution in different market segments in general, and the growth of electronic trading in particular. The concluding section discusses the possible implications of these changes for the resilience of FX markets. A box takes a close look at a crucial element of the post-trade ecosystem - how market participants mitigate FX settlement risk.

Key takeaways

- Electronification advanced most rapidly in dealer-to-customer trading, while the electronic share of inter-dealer trading decreased.

- A rise in intermediation within dealers' proprietary liquidity pools contributed to a decline in the share of "visible" FX trading in spot markets.

- Customers and dealers responded to market fragmentation by executing trades across a large number of electronic venues.

Statistical data: data behind all graphs

The feature complements the analysis of the main drivers of recent growth in global FX turnover in Schrimpf and Sushko (2019) in this issue.

An increasingly complex and fragmented market structure

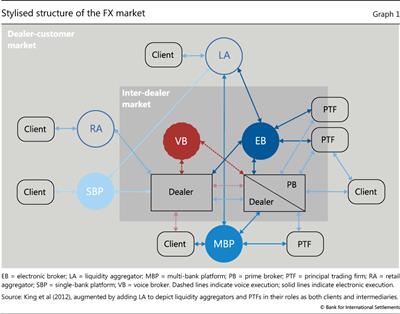

FX trading has become more complex and fragmented over the years.3 FX markets were long characterised by a two-tier structure, with clearly delineated inter-dealer and dealer-customer segments. This structure has blurred somewhat over the years (Graph 1). Financial institutions outside the bank dealer community have taken on important intermediation functions, and a plethora of electronic trading venues have emerged. These developments have led to ever greater choice in how to execute trades but also to a highly fragmented market structure.

An important catalyst of these developments was prime brokerage, whereby top FX dealers allow clients to trade directly in the bank's name with its established counterparties. Principal trading firms (PTFs) are some of the heaviest users of prime brokerage services. PTFs employ algorithmic trading strategies and have been active in FX for quite some time. What is new in recent years is that some have built a business model around making markets and thus have deeply penetrated the realm that previously was exclusive to dealers (see Schrimpf and Sushko (2019) in this issue). Prime brokered trading now accounts for a large fraction of volumes on platforms that historically catered to interbank trading, such as electronic brokers.4

Further reading

The proliferation of alternative ways to conduct trades has been spurred by customers "shopping around" for best execution and by technology providers facing lower costs to set up such platforms. Another trend has been the use of liquidity aggregators that bundle access to different trading venues or liquidity providers (Oomen (2017)). Countering this tendency, FX dealer banks, in turn, have sought to build stronger relationships with their customers. They have invested heavily in improving the technology and functionality of their proprietary trading platform offerings, known as single-bank platforms.

The resulting fragmentation of the FX market has made it harder to assess market conditions at any given point in time. Market participants wishing to trade FX have more than 75 different FX venues at their disposal (Sinclair (2018)).5 At the same time, greater internalisation of customer flow by banks (explained below) reduced the amount of inter-dealer trading via the main electronic brokers. Thus, while the market as a whole grew bigger, the share of trading activity that is "visible" to the broader market declined. Against this background, the execution methods data collected in the Triennial Survey provide a unique and rare perspective on how the structure of this crucial, yet inherently opaque, market has evolved.

Mapping out trade execution using the Triennial Survey

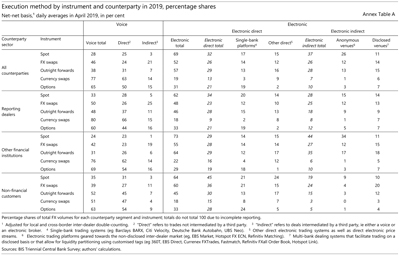

The taxonomy used in the Triennial Survey to capture data on execution methods is aligned with the main features of the market structure sketched above. At the broadest level, it distinguishes between "voice" and "electronic" execution. Within each, it further differentiates between "direct" (bilateral) and "indirect" (brokered) trading. "Direct" includes relationship-based trading by phone, trades through a chatting system, via a proprietary single-bank platform, or a direct electronic price stream. "Indirect" refers to the involvement of a third party in the matching process. This can, for instance, be a traditional voice broker, an electronic broking platform or a multi-bank platform.

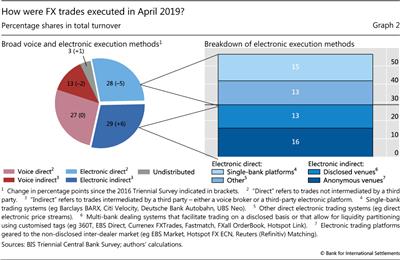

The 2019 Triennial Survey data on execution methods corroborate the picture of great diversity in trade execution choices. Electronic trading dominates, although voice remains significant in some market segments (Graph 2, left-hand panel and Annex Table A). Electronic trading was roughly equally split between "direct" and "indirect" trading in 2019, whereas "direct" electronic trading had a significantly higher market share three years earlier. Drilling down further into various forms of electronic trading, direct forms of electronic execution were about equally split between single-bank platforms and other direct forms of electronic trading, such as price streams (Graph 2, right-hand panel). When it comes to indirect electronic trading, "anonymous" venues, where counterparty identities are only revealed post-trade, attracted a slightly higher market share than "disclosed" venues, where counterparties know each other's identity before they decide to trade.

How is the landscape of FX trade execution evolving?

The main trend in FX trade execution has been increased "electronification"- deeper penetration of the market by electronic and automated trading. Electronification comes in a variety of forms, catering to the needs of a diverse set of players (fast and slow traders, banks and non-banks etc). It enables automated and continuous trading, bringing together participants with diverse trading interests so that they can more seamlessly adjust and redistribute financial exposures.

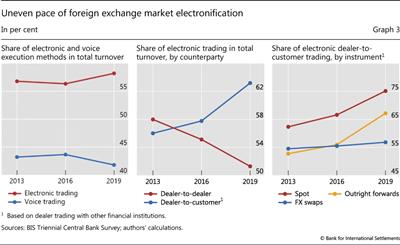

The 2019 Triennial Survey shows that the share of FX trading executed electronically edged up only slightly since the previous survey (Graph 3, left-hand panel), rising by 2 percentage points to 58% by 2019. Yet the market-wide average masks notable differences across key instruments and market segments.

Electronification progresses fastest in the dealer-customer segment

The segment where electronification progressed the fastest was dealer-to-customer transactions (Graph 3, centre panel). This rise also reflects the changing composition of market participants, with financial customers, such as hedge funds and PTFs, and lower-tier banks playing a more active role (see Schrimpf and Sushko (2019) in this issue). The dealer-customer segment has arguably also been the place where technological innovation has been the fastest, as witnessed by a greater range of trading venues featuring a diversity of execution protocols.

Spot remains the instrument with the highest electronic trading share, which stood at 75% of dealer-to-client transactions (Graph 3, right-hand panel). That said, electronic trading in forwards has been catching up at an accelerating pace.6 Non-deliverable forwards (NDFs), which are typically used for EME currencies, in particular witnessed a rapid rise in electronic trading (see Patel and Xia (2019) in this issue, Box B). Platform trading and prime-brokered access, in turn, have attracted hedge funds and PTFs to trade NDFs electronically.

Interbank electronic trading in spot declines

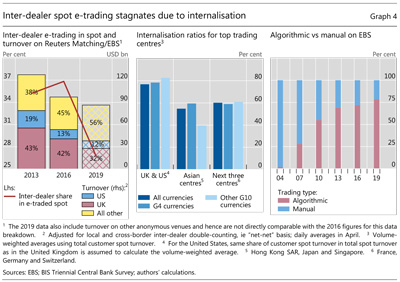

In contrast to its rise in dealer-to-customer markets, electronic spot trading in inter-dealer markets saw a decline in both relative and absolute terms, falling by 7% since 2016 to $368 billion per day in the latest Triennial Survey. As a result, inter-dealer trading accounted for less than a third of the total electronic spot market in 2019, 10 percentage points lower than in 2016 (Graph 4, left-hand panel).

This decline in electronic inter-dealer trading was driven principally by internalisation, whereby dealers temporarily warehouse risk arising from client transactions until it is offset against opposing client flow. This practice, in turn, reduces the need to offload any imbalances in inter-dealer markets. Data showed dealers reporting in the United Kingdom and the United States had some of the largest declines in electronic trading on anonymous inter-dealer venues (Graph 4, left-hand panel) and also posted some of the highest internalisation ratios for spot trades (Graph 4, centre panel).

As a consequence, electronic inter-dealer brokerage systems, which have long constituted the main locus of electronic inter-dealer trading, now only account for a small fraction of the entire market. As Evans and Rime (2019) highlight, order book depth on these platforms also declined in tandem. A likely factor has been greater algorithmic trading (Graph 4, right-hand panel), especially by PTFs (on a prime brokered basis), which tends to involve greater activity at the top of the order book. Despite this, these so-called primary venues (eg EBS Market and Reuters (Refinitiv) Matching) are still vital for FX market functioning. Primary venues still serve as an important point of price discovery (Markets Committee (2018)), and when volatility rises, internalisation becomes more challenging and dealers need these venues to manage inventory imbalances (Moore et al (2016)).

More internalisation also means that fewer trades are visible in the broader marketplace, resulting in less information leakage (Butz and Oomen (2019)). It likely led to an increase in "on-us" settlement across the books of the dealers.7 Internalisation may also partly explain why the FX industry remains highly concentrated among a few very large dealers. It may contribute to a market structure in which concentration begets more concentration: given that dealers with large flows from a diverse set of clients find it easier to internalise and can price more competitively, letting them attract ever greater customer flows. Indeed, the falling share of inter-dealer trading has gone hand-in-hand with a handful of banks coming to dominate FX volumes.8 By contrast, banks finding it hard to compete turn to other niches to retain an edge (eg providing execution algorithms to clients).

The ability of dealers to internalise benefits greatly from electronification and the ability to attract customers to trading via single-bank platforms or direct price streams. Subdued FX volatility in recent years was also conducive to internalisation. This is because there have been fewer instances of large imbalances in order flow that are difficult to match internally, thus requiring hedging on inter-dealer venues.

FX swaps still rely heavily on voice intermediation

The 2019 Triennial Survey confirms that, despite the overall trend, electronic trading is not progressing uniformly across all instruments and market segments. Most prominently, inter-dealer trading of FX swaps has remained heavily voice-reliant, while dealer-to-customer trading has moved towards greater use of electronic execution methods.

There are several interrelated reasons for voice retaining a higher share in FX swaps. First, swap trades vary greatly in size, with inter-dealer transactions at times involving particularly large notional amounts. Second, FX swaps are more difficult to price, with internal and balance sheet considerations playing a relatively larger role. The largest dealers use internal models to set their prices (eg relying on their money market desk and taking funding rates in different currencies as inputs) as opposed to sourcing price signals from wholesale venues. This means that inter-dealer FX swap trading still often relies on intermediation via voice brokers. Third, FX swap trading entails management of credit risk because it involves exchanging principal in two different currencies, at the spot rate at contract inception and at the forward rate at contract maturity. This risk needs to be managed and allocated across counterparties which, at least so far, still requires some manual processes.

By contrast, electronic trading continues to make inroads into dealer-to-customer FX swap trading. When quoting bid or ask prices to customers, dealers can rely on inter-dealer mid-prices as input. Such trading with customers is more amenable to electronification, eg by streaming prices on a single-bank platform or responding to a request-for-quote on a multi-dealer-platform.

Further fragmentation as execution spreads across secondary venues

The 2019 Triennial Survey shows that trading on multi-bank platforms (sometimes referred to as "secondary venues" to contrast them with electronic brokers, which are referred to as "primary venues") constitutes the fastest growing execution method over the past three years. Some of these secondary venues operate anonymous limit order books, akin to those on primary venues. Others cater to disclosed forms of electronic trading, where identities are known to the counterparties before they decide to engage in a trade. This allows some aspects of relationship trading to be retained, while also matching with a broader pool of potential counterparties.

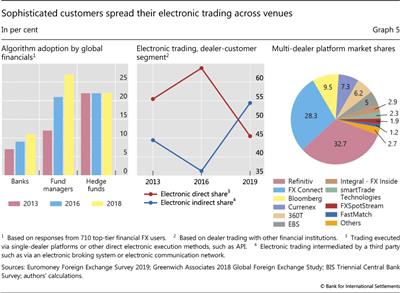

The trend towards greater reliance on methods where end users can choose from a range of liquidity providers and various ways to implement the trade is reinforced by increased attention to best execution. Sophisticated clients increasingly rely on execution algorithms to spread large orders over time and across multiple electronic venues.9 Hedge funds have been the early adopters of execution algorithms, although fund managers have followed suit (Graph 5, left-hand panel).10 As an indication of clients becoming more cost-conscious, trading on multi-bank platforms, or via liquidity aggregators bundling various venues and providers, has surpassed single-bank platform volumes and other direct forms of electronic trading (Graph 5, centre panel).11 For example, according to the 2019 Euromoney survey, buy-side customers trade using over a dozen different platform providers (Graph 5, right-hand panel).12 It is also common for top-tier liquidity providers (including non-bank market-makers) to cater to this demand by quoting simultaneously on a wide range of venues (Markets Committee (2018)).

Conclusion

FX trading has evolved rapidly over recent years. It has seen further electronification and increasing variety in trading venues and protocols. In spot, FX intermediation has tilted towards non-bank electronic market-makers, who substitute speed for balance sheet. Activity has also gravitated more to dealers' proprietary liquidity pools and away from primary inter-dealer venues. Clients can use algorithms to enhance execution and navigate a fragmented market, albeit in exchange for taking on more market risk themselves. All these developments have led to more choice for tech-savvy clients, but also to some important risk-shifting and greater market fragmentation.

Yet there are signs that fragmentation may be reaching its peak. Some customers are reportedly questioning the cost of connecting to so many venues. Dealers, too, have been re-assessing whether it is beneficial to quote prices on a large number of third-party systems. For example, a top-tier bank recently announced plans to slash the number of systems it uses, from 45 to 15. Similarly, some PTFs focused on market-making have reportedly also cut down on the number of electronic communication networks where they post prices.

Furthermore, the current market configuration has emerged largely during a prolonged period of low volatility, and its resilience might be tested if the volatility regime were to change. For example, during periods of stress, FX dealers might ration liquidity and favour clients with whom they have a strong relationship, such as those using their single-bank platform. Thus, customers who spread execution across venues could face a sharp evaporation of liquidity. The question of whose risk-bearing capacity to rely on under such circumstances could become a pertinent one. In the event of stress, the resilience of FX markets could be further challenged by the declining use of payment-versus-payment systems to reduce FX settlement risk (see box).

FX settlement risk remains significant

Morten Bech and Henry Holden

The settlement of FX trades can lead to significant risk exposures when one counterparty to a trade sends a currency payment to the other and needs to wait before receiving the currency it is buying. Over the past two decades, market participants have made significant progress in reducing FX settlement risk. Nevertheless, due in part to higher trading activity, the 2019 Triennial Survey indicates that close to $9 trillion of payments remain at risk on any given day.

The bankruptcy of Bankhaus Herstatt in 1974 demonstrated how FX settlement risk can undermine financial stability. Herstatt was a medium-sized German bank active in FX markets. At 15:30 CET on 26 June 1974, the German authorities closed the bank down. While Herstatt had already received Deutsche marks from its counterparties, it had not yet made the corresponding US dollar payments in New York. Herstatt's failure to pay led banks more generally to stop outgoing payments until they were sure their countervalues had been received. The international payment system then froze, and the erosion of trust caused lending rates to spike and credit to be curtailed.

Herstatt was a medium-sized German bank active in FX markets. At 15:30 CET on 26 June 1974, the German authorities closed the bank down. While Herstatt had already received Deutsche marks from its counterparties, it had not yet made the corresponding US dollar payments in New York. Herstatt's failure to pay led banks more generally to stop outgoing payments until they were sure their countervalues had been received. The international payment system then froze, and the erosion of trust caused lending rates to spike and credit to be curtailed.

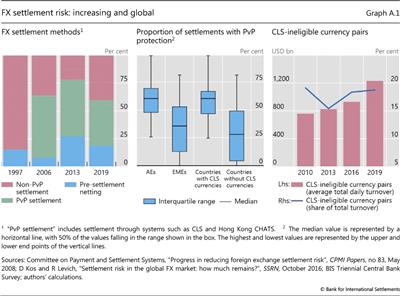

In 1996, G10 central banks endorsed a strategy to reduce FX settlement risk. The strategy involved actions to be taken by banks to control their exposures, actions to be taken by industry groups to provide services and actions to be taken by central banks to induce progress. In response, in 2002 market participants set up Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS), a specialist institution that settles FX transactions on a payment-versus-payment (PvP) basis. PvP eliminates FX settlement risk by ensuring that a payment in a currency occurs if and only if the payment in the other currency takes place. The establishment of CLS and other actions led to a big reduction in FX settlement risk. Even at the height of the Great Financial Crisis, FX markets remained resilient. However, FX settlement risk appears to have increased since 2013 in both relative and absolute terms (Graph A.1, left-hand panel).

The strategy involved actions to be taken by banks to control their exposures, actions to be taken by industry groups to provide services and actions to be taken by central banks to induce progress. In response, in 2002 market participants set up Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS), a specialist institution that settles FX transactions on a payment-versus-payment (PvP) basis. PvP eliminates FX settlement risk by ensuring that a payment in a currency occurs if and only if the payment in the other currency takes place. The establishment of CLS and other actions led to a big reduction in FX settlement risk. Even at the height of the Great Financial Crisis, FX markets remained resilient. However, FX settlement risk appears to have increased since 2013 in both relative and absolute terms (Graph A.1, left-hand panel).

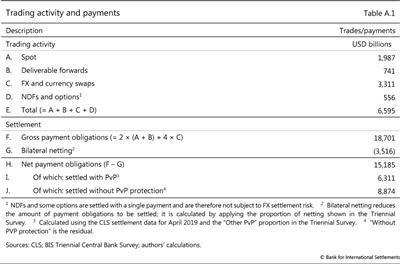

To help assess progress in reducing FX settlement risk, the Triennial Survey was expanded in 2019 to collect data on FX settlement. Different FX instruments give rise to different numbers of payments. For example, spot and outright forwards result in two payment obligations, whereas swaps result in four payments of principal (two at inception and two at repayment). Some FX transactions, such as non-deliverable forwards, are settled with a single payment and are therefore not subject to FX settlement risk. FX trades can also be bilaterally netted, which eliminates a need for settlement.

After taking account of the number of payments for each instrument, in April 2019 daily global FX trading of $6.6 trillion translated into gross payment obligations worth $18.7 trillion (Table A.1). Bilateral netting reduced the payment obligations to $15.2 trillion. About $6.3 trillion was settled on a PvP basis using CLS or a similar settlement system. This left an estimated $8.9 trillion worth of FX payments at risk on any given day. The proportion of trades with PvP protection appears to have fallen from 50% in 2013 to 40% in 2019, although available data are not fully comparable across time (Graph A.1, left-hand panel).

One reason for the relative decline in PvP protection is the growth of trading in currencies not eligible for CLS settlement. In absolute terms, 90% of FX settlement risk is in the top 10 jurisdictions. However, these advanced economies settle a higher proportion of their FX with PvP protection than emerging market economies (EMEs) do, many of which have currencies that are not included in CLS (Graph A.1, centre panel). Nonetheless, CLS-eligible currency pairs still make up about 80% of total global trading activity (Graph A.1, right-hand panel). To reduce global risk, it may therefore be necessary to both encourage FX market participants to use PvP where available and widen that availability to include EME currencies. The task of reducing global risk is now firmly on the agenda of bank supervisors.

G Galati, "Settlement risk in foreign exchange markets and CLS Bank", BIS Quarterly Review, December 2002, pp 55-65.

G Galati, "Settlement risk in foreign exchange markets and CLS Bank", BIS Quarterly Review, December 2002, pp 55-65.  Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems, "Settlement risk in foreign exchange transactions", CPMI Papers, no 17, March 1996.

Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems, "Settlement risk in foreign exchange transactions", CPMI Papers, no 17, March 1996.  Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, "Basel Committee discusses policy and supervisory initiatives and approves implementation reports", press release, October 2019.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, "Basel Committee discusses policy and supervisory initiatives and approves implementation reports", press release, October 2019.

References

Butz, M and R Oomen (2019): "Internalisation by electronic FX spot dealers", Quantitative Finance, vol 19, no 1, pp 35-56.

Euromoney (2019): Foreign Exchange Survey 2019: Electronic trading.

Evans, M and D Rime (2019): "Microstructure of foreign exchange markets", SSRN, February.

Greenwich Associates (2019): FX execution: competing in a world of algos.

Hau, H, P Hoffmann, S Langfield and Y Timmer (2019): "Discriminatory pricing of over-the-counter derivatives", IMF Working Papers, no 19/100.

King M, C Osler and D Rime (2012): "Foreign exchange market structure, players and evolution", in Handbook of Exchange Rates, edited by I Marsh, J James, and L Sarno, Hong Wiley & Sons.

Moore, M, A Schrimpf and V Sushko (2016): "Downsized FX markets: causes and implications", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 35-51.

Markets Committee (2018): "Monitoring of fast-paced electronic markets", Markets Committee Papers, no 10, September.

Oomen, R (2017): "Execution in an aggregator", Quantitative Finance, vol 17, no 3, pp 383-404.

Patel, N and D Xia (2019): "Offshore markets drive trading of emerging market currencies", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 53-67.

Schrimpf, A and V Sushko (2019): "Sizing up global foreign exchange markets", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 21-38.

Sinclair, J (2018): "Why does fragmentation continue to increase? Increasing entropy in currency markets", MarketFactory Whitepaper, February.

1 The authors would like to thank Benjamin Anderegg, Sirio Aramonte, Morten Bech, Claudio Borio, Alain Chaboud, Yin-Wong Cheung, Stijn Claessens, Jenny Hancock, Brian Hardy, Henry Holden, Wenqian Huang, Thomas Maag, Robert McCauley, Dagfinn Rime, Takeshi Shirakami, Hyun Song Shin, and Philip Wooldridge for input. We also greatly appreciate the feedback and insightful discussions with numerous market participants at major FX dealer banks, buy-side institutions, electronic market-makers and trading platforms. We are also grateful to Yifan Ma and Denis Pêtre for compiling the underlying data and Adam Cap for excellent research assistance. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements.

2 For information about the Triennial Survey, see www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx19.htm.

3 King et al (2012) illustrate the gradual build-up of complexity of the market from the 1980s through the first decade of the 2000s. We add a layer to capture further developments over the past decade.

4 Another set of players, not discussed further in this article, are retail clients (eg individuals, family offices or smaller hedge funds). Their trading needs are served by retail brokerage platforms or retail aggregators (denoted by RA in Graph 1). Their market access has become one-step removed from wholesale FX markets because of their reliance on so-called "prime-of-prime", as discussed by Moore et al (2016).

5 These venues differ in terms of the pool of participants (eg composition of fast (algorithmic) vs slow (human) traders, or banks vs non-bank players), microstructural aspects affecting latency, the order queuing or cancellation process of the platform's matching engine, "last-look" (ability of liquidity providers to reject the trade even after their price quotes are hit) policies, as well as the suite of different trading protocols.

6 The leading platform provider, EBS, introduced electronic prime brokerage for NDFs in 2016, and Reuters (Refinitiv) announced plans to introduce electronic matching for NDFs in 2020.

7 On-us settlement is where both legs of a FX transaction are settled across the books of a single institution. It is not a payment-versus-payment settlement method (see box).

8 On average, desks belonging to seven reporting banks account for 75% of FX turnover in each jurisdiction. Schrimpf and Sushko (2019) in this issue also show the inverse relationship between concentration and inter-dealer trading.

9 The cost-efficient execution of large volumes is the primary driver of execution algorithm use. With automated execution, it is the customers who bear market risk instead of dealer banks.

10 Financial clients, such as money managers, are also under considerable pressure to demonstrate best execution, with an additional push from regulatory reforms such as MiFID II. Although MiFID II is a European regulation, its global impact is highlighted in the JP Morgan Electronic Trading Trends for 2018 survey: while 73% of respondents in EMEA believe it will have an impact, 47% of respondents in the Americas and 45% in Asia-Pacific also hold the same view.

11 Academic research indicates that clients face less price discrimination when trading FX derivatives through multilateral trading platforms (Hau et al (2019)).

12 Some of the technology providers shown offer more than one platform for customer trading.